Sources Of Mauryan Empire :

- There are hardly any comprehensive contemporary accounts or literary works which refer to the Mauryan emperors though they are mentioned in various Buddhist and Jain texts as well as in some Hindu works like the brahmanas.

- The literary sources include Kautilya’s Arthasastra, Visakha Datta’s Mudra Rakshasa , Megasthenese’s Indica, Buddhist literature and Puranas.

- The archaeological sources include Ashokan Edicts and inscriptions and material remains such as silver and copper punch-marked coins.

- The Mahavamsa, the comprehensive historical chronicle in Pali from Sri Lanka, is an important additional source.

- The archaeological finds in the Gangetic regions give us solid proof about the nature of the urban centres established in the region in course of time.

- Epigraphical evidence is scanty for the period. The most widely known are the edicts of Ashoka, which have been discovered in many parts of the country.

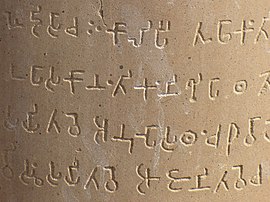

- In fact, the reconstruction of the Mauryan period to a great extent became possible only after the Brahmi script of the inscriptions at Sanchi was deciphered by James Prinsep in 1837.

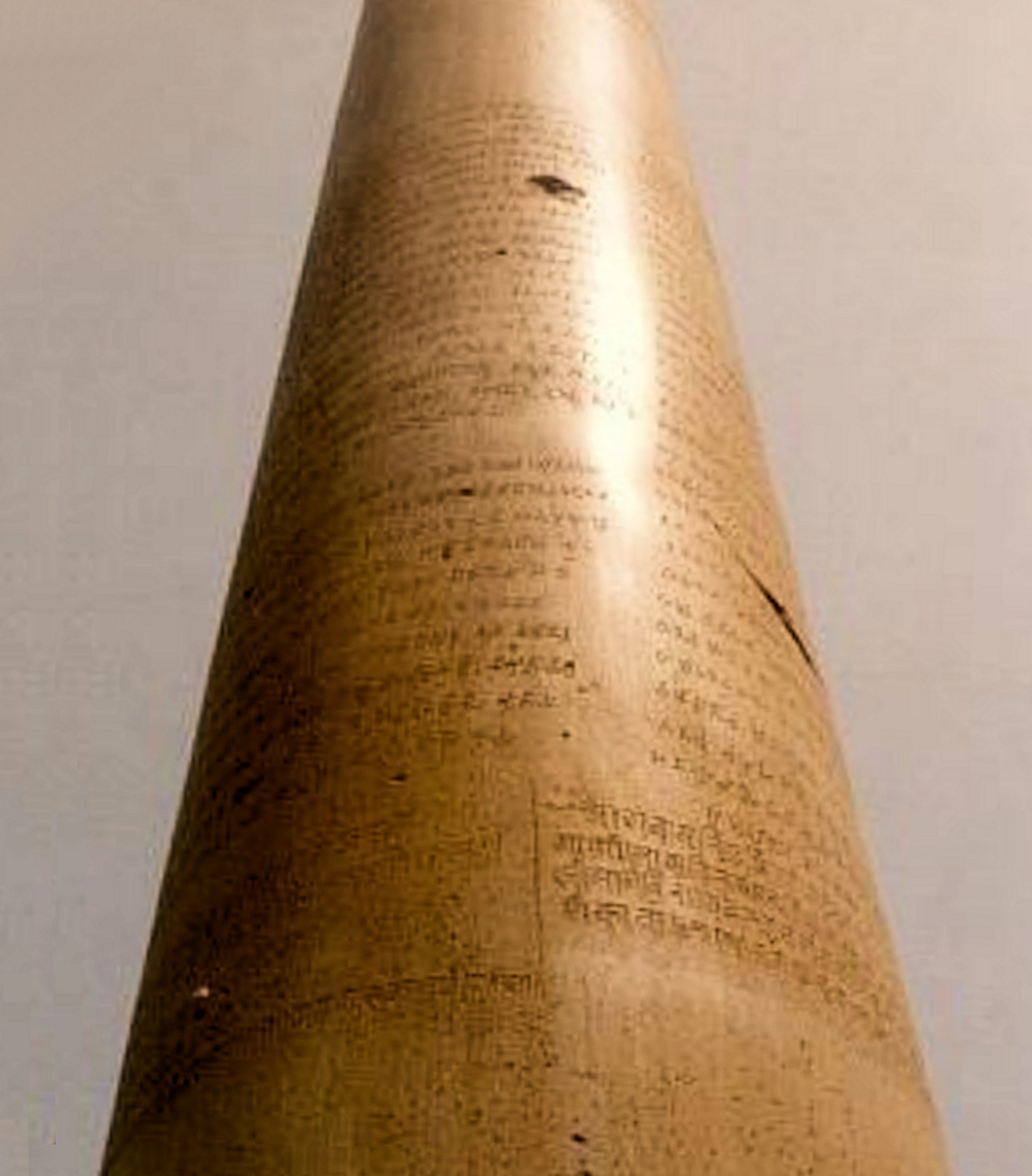

Fig : One of the major pillar Edicts

- All the edicts began with a reference to a great king, “Thus spoke devanampiya (beloved of the gods) piyadassi (of pleasing looks)”, and the geographical spread of the edicts make it clear that this was a king who had ruled over a vast empire.

- Puranic and Buddhist texts referred to a chakravartin named Ashoka. As more edicts were deciphered, the decisive identification that devananampiya piyadassi was Ashoka was made in 1915.

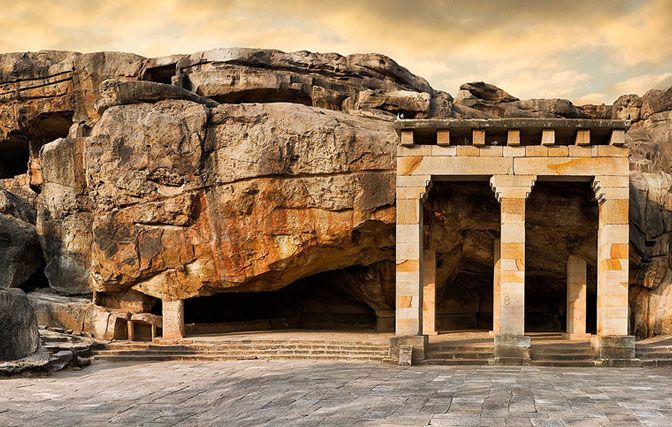

fig : Junagadh Rock Inscription

- The rock inscription of Junagadh, near Girnar in Gujarat.This was carved during the reign of Rudradaman, the local ruler and dates back to 130–150 CE. It refers to Pushyagupta, the provincial governor (rashtriya) of Emperor Chandragupta.

- This is of importance for two reasons:

- (i) it indicates the extent of the Mauryan Empire, which had expanded as far west as Gujarat and (ii) it shows that more than four centuries after his death, the name of Chandragupta was still well known and remembered in many parts of the country. A second source is a literary work.

- The play Mudrarakshasa by Visakhadatta was written during the Gupta period, sometime after the 4th century CE. It narrates Chandragupta’s accession to the throne of the Magadha Empire and the exploits of his chief advisor Chanakya or Kautilya by listing the strategies he used to counter an invasion against Chandragupta.

Mauryan Empire

- Greek historians have recorded his name as “Sandrakottus” or “Sandrakoptus”, which are evidently modified forms of Chandragupta.

- Inspired by Alexander, Chandragupta led a revolt against the Nandas years later and overthrew them.

- Chandragupta established the Mauryan Empire and became its first emperor in 321 BCE.

- Ashoka Rock Edict at Junagadh We know from the Junagadh rock inscription (referred to earlier) that Chandragupta had expanded his empire westward as far as Gujarat.

- One of his great achievements, according to local accounts, was that he waged war against the Greek prefects (military officials) left behind by Alexander and destroyed them, so that the way was cleared to carry out his ambitious plan of expanding the territories.

- Another major event of his reign was the war against Seleucus, who was one of Alexander’s generals.

- After the death of Alexander, Seleucus had established his kingdom extending up to Punjab. Chandragupta defeated him in a battle some time before 301 BCE and drove him out of the Punjab region.

- The final agreement between the two was probably not too acrimonious, since Chandragupta gave Seleucus 500 war elephants, and Seleucus sent an ambassador to Chandragupta’s court.

- This ambassador was Megasthenes, and we owe much of the information that we have about Chandragupta is Indica, the account written by Megasthenes.

Chandragupta

- Chandragupta was obviously a great ruler who had to reinvent a strong administrative apparatus to govern his extensive kingdom.

- Chandragupta was ably advised and aided by Chanakya, known for political manoeuvring, in governing his empire.

- Contemporary Jain and Buddhist texts hardly have any mention of Chanakya.

- But popular oral tradition ascribes the greatness of Chandragupta and his reign to the wisdom and genius of Chanakya. Chanakya, also known as Kautilya and Vishnugupta, was a Brahmin and a sworn adversary of the Nandas.

- He is credited with having devised the strategy for overthrowing the Nandas and helping Chandragupta to become the emperor of Magadha. He is celebrated as the author of the Arthasastra, a treatise on political strategy and governance.

- His intrigues and brilliant strategy to subvert the intended invasion of Magadha is the theme of the play, Mudrarakshasa.

Bindusara

- Chandragupta’s son Bindusara succeeded him as emperor in 297 BCE in a peaceful and natural transition. We do not know what happened to Chandragupta.

- He probably renounced the world. According to the Jain tradition, Chandragupta spent his last years as an ascetic in Chandragiri, near Sravanabelagola, in Karnataka. Bindusara was clearly a capable ruler and continued his father’s tradition of close interaction with the Greek states of West Asia.

- He continued to be advised by Chanakya and other capable ministers. His sons were appointed as viceroys of the different provinces of the empire. We do not know much about his military exploits, but the empire passed intact to his son, Ashoka.

- Bindusara ruled for 25 years, and he must have died in 272 BCE.

- Ashoka was not his chosen successor, and the fact that he came to the throne only four years later in 268 BCE would indicate that there was a struggle between the sons of Bindusara for the succession.

- Ashoka had been the viceroy of Taxila when he put down a revolt against the local officials by the people of Taxila, and was later the viceroy of Ujjain, the capital of Avanti and a major city and commercial centre.

- As emperor, he is credited with building the monumental structures that have been excavated in the site of Pataliputra.

- He continued the tradition of close interaction with the Greek states in West Asia, and there was mutual exchange of emissaries from both sides.

Ashoka

- The defining event of Ashoka’s rule was his campaign against Kalinga (present-day Odisha) in the eighth year of his reign. This is the only recorded military expedition of the Mauryas.

- The number of those killed in battle, those who died subsequently, and those deported ran into tens of thousands.

- The campaign had probably been more ferocious and brutal than usual because this was a punitive war against Kalinga, which had broken away from the Magadha Empire (the Hathigumpha inscription speaks of Kalinga as a part of the Nanda Empire).

Fig : Hathigumpha Inscription

- Ashoka was devastated by the carnage and moved by the suffering that he converted to humanistic values.

- He became a Buddhist and his new-found values and beliefs were recorded in a series of edicts, which confirm his passion for peace and moral righteousness or dhamma (dharma in Sanskrit).

Edicts of Ashoka

Fig : Ashoka Edicts

- The edicts of Ashoka thus constitute the most concrete source of information about the Mauryan Empire.

- There are 33 edicts comprising 14 Major Rock Edicts, 2 known as Kalinga edicts, 7 Pillar Edicts, some Minor Rock Edicts and a few Minor Pillar Inscriptions.

- The Major Rock Edicts extend from Kandahar in Afghanistan, Shahbazgarhi and Mansehra in northwest Pakistan to Uttarakhand district in the north, Gujarat and Maharashtra in the west, Odisha in the east and as far south as Karnataka and Kurnool district in Andhra Pradesh. Minor Pillar Inscriptions have been found as far north as Nepal (near Lumbini).

- The edicts were written mostly in the Brahmi script and in Magadhi and Prakrit.

Fig : Brahmi Script

- The Kandahar inscriptions are in Greek and Aramaic, while the two inscriptions in north-west Pakistan are in Kharosthi script.

- The geographical spread of the edicts essentially defines the extent of the vast empire over which Ashoka ruled.

- The second inscription mentions lands beyond his borders: “the Chodas (Cholas), the Pandyas, the Satiyaputa, the Keralaputa (Chera), even Tamraparni, the Yona king Antiyoka (Antiochus), and the kings who are the neighbours of this Antioka”.

- The edicts stress Ashoka’s belief in peace, righteousness and justice and his concern for the welfare of his people.

- By rejecting violence and war, advocating peace and the pursuit of dhamma, Ashoka negated the prevailing philosophy of statecraft that stressed that an emperor had to strive to extend and consolidate his empire through warfare and military conquests.

Major Edicts of Ashoka :

Major Rock Edict 1 : Prohibition Of animal slaughtering especially during festivals.

Major Rock Edict 2 : Information about Kingdoms of South India like Chola, Pandyas, Satyapura and Keralputra.

Major Rock Edict 3 : Says about the role of Yuktas (subordinate officers and Pradesikas (district Heads) along with Rajukas (Rural officers) to spread the Dhamma Policy of Asoka.

Major Rock Edict 4 : Says about the impact of Dhamma in the society .

Major Rock Edict 5 : It says about appointment of Dhammamahamatras and also his concerns about slaves.This edicts informs Ashokas words ” Every Human Is My Child “.

Major Rock Edict 6: This edicts talks about the welfare measures and its informations.

Major Rock Edict 7:This says about the tolerance towards all religions.

Major Rock Edict 8:It describes Asoka’s first Dhamma Yatra to Bodhgaya & Bodhi Tree .

Major Rock Edict 9 : It condemns different ceremonies followed during that time.

Major Rock Edict 10 : It confirms with the policy of dhamma.

Major Rock Edict 11 : Says about preventing killing of animals.

Major Rock Edict 12 : Request to have tolerance towards all religions.

Major Rock Edict 13: This rock edict pleads the way of conquest which is dhamma instead of war.

Major Rock Edict 14 : It describes engraving of inscriptions in different parts of country.

Third Buddhist Council

- One of the major events of Ashoka’s reign was the convening of the Third Buddhist sangha (council) in 250 BCE in the capital Pataliputra.

- Ashoka’s deepening commitment to Buddhism meant that royal patronage was extended to the Buddhist establishment.

- An important outcome of this sangha was the decision to expand the reach of Buddhism to other parts of the region and to send missions to convert people to the religion.

- Buddhism thus became a proselytizing religion and missionaries were sent to regions outlying the empire such as Kashmir and South India.

- According to popular belief, Ashoka sent his two children, Mahinda and Sanghamitta, to Sri Lanka to propagate Buddhism.

- It is believed that they took a branch of the original bodhi tree to Sri Lanka.

- Ashoka died in 231 BCE. Sadly, though his revolutionary view of governance and non-violence find a resonance in our contemporary sensibilities, they were not in consonance with the realities of the times.

- After his death, the Mauryan Empire slowly disintegrated and died out within fifty years. But the two centuries prior to Ashoka’s death and the disintegration of the Mauryan Empire were truly momentous in Indian history.

- This was a period of great change. Ashoka’s visit to the Ramagrama Sanchi Stupa Southern Gate The consolidation of a state extending over nearly two-thirds of the sub-continent had taken place with formalised administration, development of bureaucratic institutions and economic expansion, in addition to the rise of new heterodox religions and philosophies that questioned the established orthodoxy.

The Mauryan State and Polity

- The major areas of concern for the Mauryan state were the collection of taxes as revenue to the state and the administration of justice, in addition to the maintenance of internal security and defence against external aggression.

- This required a large and complex administrative machinery and institutions.

- Greek historians, taking their lead from Megasthenes, described the Mauryan state as a centralised state. What we should infer from this description as a centralised state is that a uniform pattern of administration was established throughout the very large area of the empire.

- But, given the existing state of technology in communications and transport, a decentralised administrative system had to be in place. This bureaucratic set-up covered a hierarchy of settlements from the village, to the towns, provincial capitals and major cities.

Sthanika: Tax collectors working under Pradeshikas.

Durgapala: Governors of forts.

Antapala: Governors of frontiers.

Akshapatala: Accountant General

Lipikaras: Scribes

- The bureaucracy enabled and required an efficient system of revenue collection, since it needed to be paid out of taxes collected. Equally, the very large army of the Mauryan Empire could be maintained only with the revenue raised through taxation.

- The large bureaucracy also commanded huge salaries. According to the Arthasastra, the salary of chief minister, the purohita and the army commander was 48,000 panas, and the soldiers received 500 panas.

- If we multiply this by the number of infantry and cavalry, we get an idea of the enormous resources needed to maintain the army and the administrative staff.

Navadhyaksha: Superintendent of ships

Lohadhyaksha: Superintendent of iron

Pauthavadhyakhsa: Superintendent of weights and measures

Akaradhyaksha: Superintendent of mines

Vyavharika Mahamatta: Judiciary officers

Pulisanj: Public relations officers

There were also agents called Vishakanyas (poisonous girls).

Arthasastra

- Perhaps the most detailed account of the administration is to be found in the Arthasastra (though the work itself is now dated to a few centuries later).

- However, it must be remembered that the Arthasastra was a prescriptive text, which laid down the guidelines for good administration. If we add to this the information from Ashoka’s edicts and the work of Megasthenes, we get a more comprehensive picture of the Mauryan state as it was.

Provincial Administration

- At the head of the administration was the king. He was assisted by a council of ministers and a purohita or priest, who was a person of great importance, and secretaries known as mahamatriyas.

- The capital region of Pataliputra was directly administered. The rest of the empire was divided into four provinces based at Suvarnagiri (near Kurnool in Andhra Pradesh), Ujjain (Avanti, Malwa), Taxila in the northwest, and Tosali in Odisha in the southeast.

- The provinces were administered by governors who were usually royal princes. In each region, the revenue and judicial administration and the bureaucracy of the Mauryan state was replicated to achieve a uniform system of governance.

- Revenue collection was the responsibility of a collector-general (samaharta) who was also in charge of exchequer that he was, in effect, like a minister of finance. He had to supervise all the provinces, fortified towns, mines, forests, trade routes and others, which were the sources of revenue.

- The treasurer was responsible for keeping a record of the tax revenues.

- The accounts of each department had to be presented jointly by the ministers to the king. Each department had a large staff of superintendents and subordinate officers linked to the central and local governments.

Yuvaraj: The crown prince

Purohita: The chief priest

The Senapati: The commander in chief

Amatya: Civil servants and few other ministers.

District and Village Administration

- At the next level of administration came the districts, villages and towns. The district was under the command of a sthanika, while officials known as gopas were in charge of five to ten villages. Urban administration was handled by a nagarika.

- Villages were semi-autonomous and were under the authority of a gramani, appointed by the central government, and a council of village elders. Agriculture was then, as it remained down the centuries, the most important contributor to the economy, and the tax on agricultural produce constituted the most important source of revenue.

- Usually, the king was entitled to one-sixth of the produce. In reality, it was often much higher, usually about one-fourth of the produce.

Sannidhata: Chief treasury

Samaharta: collector general of revenue.

The jail was known as Bandhangara

it was different from lock-up called Charaka.

Source of Revenue

- The Arthasastra, recommended comprehensive state control over agricultural production and marketing, with warehouses to store agricultural products and regulated markets, in order to maximise the revenues from this most important sector of the economy.

- Other taxes included taxes on land, on irrigation if the sources of irrigation had been provided by the state, taxes on urban houses, customs and tolls on goods transported for trade and profits from coinage and trade operations carried on by the government.

- Lands owned by the king, forests, mines and manufacture and salt, on which the state held a monopoly, were also important sources of revenue. Judicial Administration Justice was administered through courts, which were established in all the major towns. Two types of courts are mentioned.

- The dharmasthiya courts mostly dealt with civil law relating to marriage, inheritance and other aspects of civil life. The courts were presided over by three judges wellversed in sacred laws and three amatyas (secretaries).

- Another type of court was called kantakasodhana (removal of thorns), also presided over by three judges and three amatyas.

- The main purpose of these courts was to clear the society of anti-social elements and various types of crimes, and it functioned more like the modern police, and relied on a network of spies for information about such antisocial activities.

- Punishments for crimes were usually quite severe. The overall objective of the judicial system as it evolved was to extend government control over most aspects of ordinary life.

Ashoka’s Dharmic State

- Ashoka’s rule gives us an alternative model of a righteous king and a just state.

- He instructed his officials, the yuktas (subordinate officials), rajjukas (rural administrators) and pradesikas (heads of the districts) to go on tours every five years to instruct people in dhamma (Major Rock Edict 3).

- Ashoka’s injunctions to the officers and city magistrates stressed that all the people were his children and he wished for his people what he wished for his own children, that they should obtain welfare and happiness in this world and the next.

- These officials should recognise their own responsibilities and strive to be impartial and see to it that men were not imprisoned or tortured without good reason.

- He added that he would send an officer every five years to verify if his instructions were carried out (Kalinga Rock Edict 1).

- Ashoka realised that an effective ruler needed to be fully informed about what was happening in his kingdom and insisted that he should be advised and informed promptly wherever he might be (Major Rock Edict 6).

- He insisted that all religions should co-exist and the ascetics of all religions were honoured (Major Rock Edicts 7 and 12).

- Providing medical care should be one of the functions of the state, the emperor ordered hospitals to be set up to treat human beings and animals (Major Rock Edict 2).

- Preventing unnecessary slaughter of animals and showing respect for all living beings was another recurrent theme in his edicts.

- In Ashoka’s edicts, we find an alternative humane and empathetic model of governance. The edicts stress that everybody, officials as well as subjects, act righteously following dhamma

Agriculture

- Agriculture formed the backbone of the economy. It was the largest sector in terms of its share in total revenue to the state and employment.

- The Greeks noted with wonder that two crops could be raised annually in India because of the fertility of the soil. Besides food grains, India also grew commercial crops such as sugarcane and cotton, described by Megasthenes as a reed that produced honey and trees on which wool grew. These were important commercial crops.

- The fact that the agrarian sector could produce a substantial surplus was a major factor in the diversification of the economy beyond subsistence to commercial production.

Crafts and Goods

- Many crafts producing a variety of manufactures flourished in the economy. We can categorise the products as utilitarian or functional, and luxurious and ornamental.

- Spinning and weaving, especially of cotton fabrics, relying on the universal availability of cotton throughout India, were the most widespread occupations outside of agriculture.

- A great variety of cloth was produced in the country, ranging from the coarse fabrics used by the ordinary people for everyday use, to the very fine textures worn by the upper classes and the royalty.

- The Arthasastra refers to the regions producing specialised textiles – Kasi (Benares), Vanga (Bengal), Kamarupa (Assam), Madurai and many others. Each region produced many distinctive and specialised varieties of fabrics. Cloth embroidered with gold and silver was worn by the King and members of the royal court.

- Silk was known and was generally referred to as Chinese silk, which also indicates that extensive trade was carried on in the Mauryan Empire.

- Metal and metal works were of great importance, and the local metal workers worked with iron, copper and other metals to produce tools, implements, vessels and other utility items.

- Iron smelting had been known for many centuries, but there was a great improvement in technology after about 500 BCE, which made it possible to smelt iron in furnaces at very high temperatures.

- Archaeological finds show a great qualitative and quantitative improvement in iron production after this date.

- Improvement in iron technology had widespread implications for the rest of the economy.

- Better tools like axes made more extensive clearing of forests possible for agriculture; better ploughs could improve agricultural processes; better nails and tools improved woodwork and carpentry as well as other crafts.

- Woodwork was another important craft for ship-building, making carts and chariots, house construction and so on. Stone work–stone carving and polishing– had evolved as a highly skilled craft.

- This expertise is seen in the stone sculptures in the stupa at Sanchi and the highly polished Chunar stone used for Ashoka’s pillars. Sanchi Stupa

- A whole range of luxury goods was produced, including gold and silver articles, jewellery, perfumes and carved ivory. There is evidence that many other products like drugs and medicines, pottery, dyes and gums were produced in the Mauryan Empire.

- The economy had thus developed far beyond subsistence production to a very sophisticated level of commercial craft production. Crafts were predominantly urbanbased hereditary occupations and sons usually followed their fathers in the practice of various crafts.

- Craftsmen worked primarily as individuals, though royal workshops for producing cloth and other products also existed. Each craft had a head called pamukha (pramukha or leader) and a jettha (jyeshtha or elder) and was organised in a seni (srenior a guild), so that the institutional identity superseded the individual in craft production.

- Disputes between srenis were resolved by a mahasetthi, and this ensured the smooth functioning of craft production in the cities.

Trade

- Trade or exchange becomes a natural concomitant of economic diversification and growth. Production of a surplus beyond subsistence is futile unless the surplus has exchange value, since the surplus has no use value when subsistence needs have been met.

- Thus, as the economy diversified and expanded, exchange becomes an important part of realising the benefits of such expansion.

- Trade takes place in a hierarchy of markets, ranging from the exchange of goods in a village market, between villages and towns within a district, across cities in long-distance overland trade and across borders to other countries.

- Trade also needs a conducive political climate as was provided by the Mauryan Empire, which ensured peace and stability over a very large area. The rivers in the Gangetic plains were major means for transporting goods throughout northern India.

- Goods were transported further west overland by road. Roads connected the north of the country to cities and markets in the south-east, and in the south-west, passing through towns like Vidisha and Ujjain.

- The north-west route linked the empire to central and western Asia. Overseas trade by ships was also known, and Buddhist Jataka tales refer to the long voyages undertaken by merchants.

- Sea-borne trade was carried on with Burma and the Malay Archipelago, and with Sri Lanka. The ships, however, were probably quite small and might have hugged the coastline.

- We do not have much information about the merchant communities. In general, long-distance overland trade was undertaken by merchant groups travelling together as a caravan for security, led by a caravan leader known as the mahasarthavaha.

- Roads through forests and unfavourable environments like deserts were always dangerous. The Arthasastra, however, stresses the importance of trade and ensuring its smooth functioning.

- Trade has to be facilitated through the construction of roads and maintaining them in good condition. Since tolls and octroi were collected on goods when they were transported, toll booths must have been set up and manned on all the trade routes.

- Urban markets and craftsmen were generally closely monitored and controlled to prevent fraud. The Arthasastra has a long list of the goods – agricultural and manufactured – which were traded in internal and foreign trade.

- These include textiles, woollens, silks, aromatic woods, animal skins and gems from various parts of India, China and Sri Lanka. Greek sources confirm the trade links with the west through the Greek states to Egypt. Indigo, ivory, tortoiseshell, pearls and perfumes and rare woods were all exported to Egypt.

Coins and Currency

- Though coinage was known, barter was the medium of exchange in pre-modern economies.

- In the Mauryan Empire, the silver coin known as pana and its sub-divisions were the most commonly used currency.

- Hordes of punch-marked coins have been found in many parts of north India, though some of these coins may have been from earlier periods. Thus while coins were in use, it is difficult to estimate the extent to which the economy was monetised.

Process of Urbanisation

- Urbanisation is the process of the establishment of towns and cities in an agrarian landscape. Towns can come up for various reasons – as the headquarters of administration, as pilgrim centres, as commercial market centres and because of their locational advantages on major trade routes.

- In what way do urban settlements differ from villages or rural settlements? To begin with, towns and cities do not produce their own food and depend on the efficient transfer of agricultural surplus for their basic consumption needs.

- A larger number of people reside in towns and cities and the density of population is much higher in cities.

- Cities attract a variety of non-agricultural workers and craftsmen, who seek employment, thereby forming the workforce for the production of manufactured goods and services of various kinds. These goods, in addition to the agricultural products brought in from the rural countryside, are traded in markets.

- Cities also tend to house a variety of persons in service-related activities. The sangam poetry in Tamil and the Tamil epics provide vivid pictures of cities like Madurai, Kanchipuram and Poompuhar as teeming with people, with vibrant markets and merchants selling a variety of goods, as well as vendors selling various goods including food door to door.

- Though these literary works relate to a slightly later period, it is not different in terms of the prevailing levels of technology, and these descriptions may be taken as an accurate depiction of urban living.

- The only contemporary pictorial representation of cities is found in the sculptures in Sanchi, which portray royal processions, and cities are seen to have roads, a multitude of people and multistoreyed buildings crowded together.

Art and Culture

- Most of the literature and art of the period have not survived. Sanskrit language and literature were enriched by the work of the grammarian Panini (c. 500 BCE), and Katyayana, who was a contemporary of the Nandas and had written a commentary on Panini’s work.

- Buddhist and Jain texts were primarily written in Pali.

- Evidently many literary works in Sanskrit were produced during this period and find mention in later works, but they are not available to us. The Arthasastra notes the performing arts of the period, including music, instrumental music, bards, dance and theatre.

- The extensive production of crafted luxury products like jewellery, ivory carving and wood work, and especially stone carving should all be included as products of Mauryan art.

- Many religions, castes and communities lived together in harmony in the Mauryan society. There is little mention of any overt dissension or disputes among them.

- As in many regions of that era (including ancient Tamil Nadu), courtesans were accorded a special place in the social hierarchy and their contributions were highly valued.